because we destroyed ourselves

Why America's ongoing social dissolution and the merging of Islamic fundamentalism with dissatisfied minorities can be traced back to the War on Drugs and its tentacles of social control.

All the way back in 2006, far before being woke was cool, I walked away from my counterterrorism analysis job at the NSA and took on nearly $90,000 in debt to write a book arguing that the greatest threat America faced when it came to terrorism wouldn’t be outsiders coming in, but instead would be radicalized ex-cons merging with fundamentalist Islam while in prison, and then emerging to wage war against the establishment as an insurgency.

This seemed inevitable due to the many generations of economic disadvantage suffered by African-Americans, a trend that can be traced back directly to the genesis of the War on Drugs. And so as America’s countless social schisms continue to widen and the forces of Islamic fundamentalist terror consolidate themselves for another wave of attacks on the West, keep in mind that all of this has been a long time coming.

As our financial crisis deepens and the schisms between the haves and the have-nots continue to open, American drug laws and the prison system they’ve perpetuated are beginning to gather an increasingly harsh spotlight. But so what. It’s not like the War on Drugs, which started over forty-years ago in 1973, has done anything to increase the growing level of economic disparity in America… right?

A lot happened in 1973.

It was a few years after Nixon slammed the gold window shut, the waning hours of a decapitated Civil Rights movement, and the year we began to disentangle ourselves from Vietnam. But it also marks the genesis of the War on Drugs: the year the Rockefeller Drug Laws were passed. And that same year something funny happened: the income gap between black and white began to widen back out, instead of closing – as it had been up until 1973.

Did the start of the War on Drugs play a significant role in creating our present economic and social realities – where the average black family has eight-cents of wealth for every dollar owned by whites, and a black child is nine-times more likely than a white child to have a parent in prison?

Not having both parents around can be directly linked to any number of issues, in fifty-years of international studies of over 10,000 subjects, researchers haven’t been able to find “any other class of experience that has as strong and consistent effect on personality and personality development as does the experience of [parental] rejection… children who were often rejected by their parents tend to feel more anxious and insecure, as well as more hostile and aggressive toward others.” And surprisingly enough, the study showed that fatherly affection, or lack thereof, may shape our personality even more than attention from our mothers.

Just how damaging is it for a child to grow up in a fatherless home? Well, they produce: 71% of our high school drop-outs, 85% of the kids with behavioral disorders, 90% of our homeless and runaway children, 75% of the adolescents in drug abuse programs, and a striking majority in one final category. Out of all the kids in our juvenile detention facilities, 85% of them come from fatherless homes.

If your Dad’s in prison there’s an extraordinary high chance that you too will someday end up behind bars, creating a cycle of absence that has been perpetuating for two-generations within the African-American community.

And yet everyone from Bill Cosby to Ronald Reagan seems fond of placing the blame for our black community’s fate squarely on the shoulders of African-Americans, largely excusing the rest of America from any blame for their plight and refusing to consider that – just maybe – other factors might have come into play at some point during our shared history.

For the most part, the emergence of the modern Welfare State in particular has been singled-out as the single most detrimental force within our African-American community, since it supposedly allowed “welfare queens” with “80 names, 30 addresses, and 12 Social security cards” to pull in over $150,000 of tax-free income a year. As the argument goes, the Public Welfare Amendments of 1962 created a system that disincentived marriage by rewarding single mothers with loads of free cash.

All they had to do was remain out of wedlock, and the checks would just keep on rolling in.

This view was popularized by a Nobel Prize winning physicist, William Shockley, who argued that these programs “tended to encourage childbirth, especially among less productive members of society (particularly blacks, whom he considered to be genetically inferior to whites), causing a reverse evolution.” Shockley popularized this hypothesis, bringing it to both Congress and the public, and even put forth a proposal offering financial rewards to minorities if they were voluntary sterilized.

So assuming that the Welfare State was created by black mothers who had no intent to ever marry, and willfully popped out babies to get paid, we’d expect to see a steady even rise in the rate of single black mothers starting right around 1962, when the Public Welfare Amendments were passed. And yet Welfare didn’t have anything to do with the destruction of the black family, it would take a decade for a different phenomenon to emerge and remove black fathers from the picture entirely and create the familial reality that African-Americans have lived in for the past two generations.

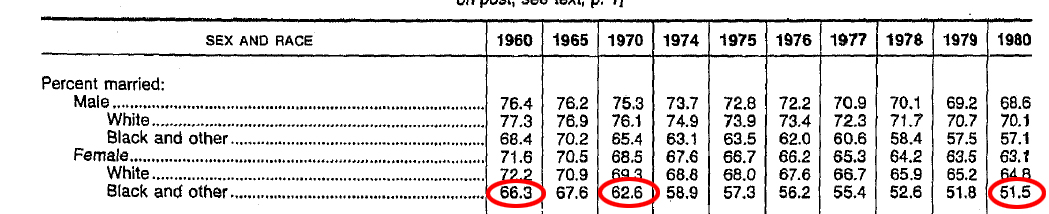

In the decade prior to the start of the War on Drugs, the first decade of the Public Welfare Amendments, the percentage of married African-American women roughly followed the national trend and declined proportionally by less than 6% – but then in the ’70s, as the national average rate remained stable, the proportional decline for African-American women tripled to nearly 18%:

(66.3 – 62.6 = 3.7% | 3.7 / 66.3 = 5.5% and 62.6 – 51.5 = 11.1% | 11.1 / 62.6 = 17.7%)

Seems a bit odd. Did it just take a full decade for black women to finally realize that all they had to do was pop out a baby or seven, marriage be damned, and they could start rolling in the dough? Or maybe something else happened that created a dearth of African-American men who were available to actually marry?

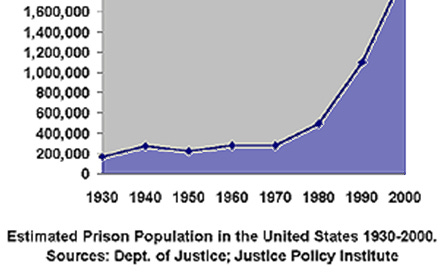

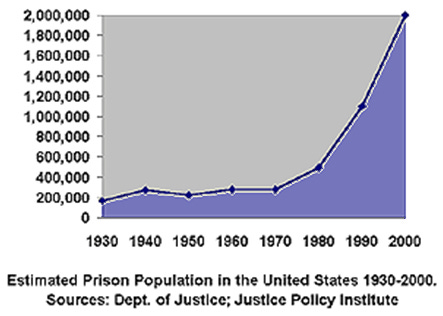

In 1971 President Nixon officially began the War on Drugs, which fully hit its stride in ’73 with the passage of the draconian Rockefeller Drugs Laws, and very quickly a distinct trend in the American prison population emerged:

And how would this spike affect the marriage rates of black folks? Well, if you’re familiar with American drug laws, it shouldn’t surprise you that some 90% of those arrested under the Rockefeller Drug Laws in the years after its passage were minorities. This baseline source of our prison population has persisted up until today, when over half of those in federal prison are serving time for a drug offense.

Sure, correlation doesn’t prove causation – but when you stop a moment and consider that marriage requires an eligible male, it’s not that hard to figure out why the black family begin to disintegrate just as our War on Drugs began, as it’s a little bit difficult to marry someone behind bars. And just how many African-American males were sent behind bars in the decades following the start of the War on Drugs?

A black male born in 1974 had a 13.4% chance of going to prison at some point in his life, while a white male had just a 2.2% chance. And it’s not like this trend got any better, by 1991 the odds a black male would spend time in prison had ballooned to 29%, while the odds a white male would end up in the clink had only increased to 4.4%

Today roughly 12% of the American population is black and yet about half of the two-million Americans locked up in prison are black. And at any one time in America, almost a third of black American males in their twenties are under some form of “correctional supervision” – if not actually incarcerated, then either on probation or on parole, meaning they’ve recently passed through the American penal system.

This means that as of 1996, a sixteen-year-old kid in America would have nearly a one-in-three chance of spending some time behind bars if he was unlucky enough to have been born black. If he happened to be born white, he’d only face a 4% chance of incarceration – a disparity that’s been steadily increasing since then. In Chicago’s home state there are 10,000 more black prisoners than black college students, and for every two black students enrolled in college there are five elsewhere in the state either locked up or on parole.

The explanation is not that blacks simply use drugs at a higher rate than whites. If anything, studies have shown that whites, “particularly white youths, are more likely to engage in drug crime than people of color.” Surveys published by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse reported that compared to black students: white students were seven times as likely to use cocaine, eight times as likely to use crack cocaine, seven times as likely to use heroin, and were 33% more likely to have sold illegal drugs.

So it’s not all that difficult to see how the reduction in marriageable males effectively gutted African-American families. What’s also perfectly clear is how the growth of the American Prison State affected government welfare expenditures, and led directly to the emergence of our Modern Welfare State.

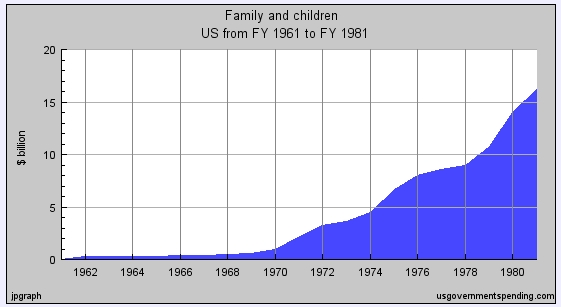

Welfare spending on families and children also witnesses a distinct spike during these same years – but it starts in the early ’70s not the early ’60s when the Public Welfare Amendments were first passed. Neither population growth nor total welfare spending explain this spike, both grew at a relatively flat linear rate during this time period.

If the growth of our Welfare State was caused simply by the laws funding it being passed, you’d expect to see American government expenditures on welfare funding sent to families and children spike in 1962, and then grow into the next few decades. 1962′s the year the Public Welfare Amendments were passed, which specifically increased aid to dependent children.

But that’s not what happened at all:

If the War on Drugs didn’t directly precipitate the destruction of the African-American family, why did the decline in married black women triple during the first decade of the War? And why did welfare spending spike in lockstep with our prison population right as it started?

We’ve certainly come a long way as a nation since Abolition, but the horrible reality is that a black child who was born during slavery was more likely to be raised by both parents than a black child born during the twenty-first century. As Fredrick Douglass explained, during slavery it was common practice to separate children born into slavery from their birth-mothers before their first birthday. Which makes perfect sense when you consider that under slavery blacks were human chattel, and separating newborns calves from their mothers is just what you do with livestock.

Things had been looking up for black families, back in 1963 as MLK gave his “I Have A Dream” speech about 70% of black families were headed by a married couple. But that percentage steadily began to drop, between 1970 and 2001 it declined by 34%, double the white decline, and by 2002 it had bottomed out at just 48%.

In fact, the impact of the War on Drugs has been so racially biased that in 2006 America had nearly six-times the proportion of its black population in prison than South Africa did at the height of Apartheid. And our penal system has grown so massive that the U.S. criminal justice system now employs more people than America’s two largest private employers, Wal-Mart and McDonald’s, combined.

And although only 14% of all illicit drug users are black, blacks make up over half of those in prison for drug offenses. A black man is eight-times as likely as a white man to be locked up at some point in his life.

After all, drug laws in America “have originally been based on racism… all of these laws are based on the belief that there is a class in society that can control themselves, and there is a class in society which cannot.” Nixon’s public motivation for the War on Drugs is that it was a response to the growing numbers of military serviceman who were getting hooked on heroin and other narcotics while serving in the Vietnam War.

Although that was a troublesome issue, when you know the history of all past American drugs laws it quickly becomes apparent that there’s no way in hell drug-using veterans was the only impetus behind this wave of anti-drug legislation, and that Nixon was using soldiers’ addiction as opportunistic displacement – especially when you consider that only 4.5% of returning servicemen tested positive for heroin. As one Nixon’s Chief of Staff wrote in his diary: “Nixon emphasized that you have to face the fact the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognises this while not appearing to.”

And if there’s any doubt about the weight that quote might have had on legislation, here are Nixon’s own words on abortion: “There are times when an abortion is necessary. I know that. ” And when exactly would that be? “When you have a black and a white.”

As the Arab world is wracked by the spasms of popular violence brought on by their social and economic inequality, many Americans have begun to stop and consider the possibility that violent fissures in our own society may begin to open. Much has been made of the emerging upperclass in American society, but the reality is that with the median white family having over twenty-times as much wealth as a black family – no economic disparity is starker than the one that correlates directly with race.

In the same way that the Arab Street finally erupted when food prices simply became too much, is there a timer on our own innercities ticking down as food stamp use and food inflation continue to skyrocket? Could a wave of urban homegrown terrorism erupt in American cities once our urban poor finally reach a tipping point and decide to lash out?

Maybe it doesn’t mean much to you that the average black family has eight-cents of wealth for every dollar of wealth owned by whites, that the the ongoing recession has doubled the wealth gap between blacks and whites, or that the unemployment rate of blacks is edging up on twice as high as the white rate – easily surpassing it when you count incarcerated blacks. After all, a black child in American is nine-times more likely than a white child to have a parent who’s locked up.

But let’s look into the data and the implications a little bit more.

The precise era that saw a drug-law fueled explosion in our prison population, the early 1970s, are the exact same years that the economic situation of blacks began to starkly worsen and that the gap between rich and poor is wrenched wide open. Beginning in those years and continuing into today, “the economic status of black compared to that of whites has, on average, stagnated or deteriorated.”

Up until 1973, the precise year the Rockefeller Drug Laws were passed, the difference between black and white median income had been closing. But then that year it changed course, and in “an ominous bellwether… the gap between black and white incomes started to grow wider again, in both absolute and relative terms.” Direct empirical research into incarceration’s economic effects weren’t done until recently, when a Pew Charitable Trusts research paper showed that prior to imprisonment two-thirds of male inmates were employed and half were their family’s primary source of income. Additionally, upon release an ex-con’s annual earnings were reduced by 40%

In the nearly forty years since America’s modern drug laws were passed, there has been a massive increase in economic inequality by any measure. In the early 1970′s not only did the income gap between black and white begin to widen again, it also becomes much more top-heavily favored to the very rich – who happen to be almost exclusively white as well.

With home equity making up 44% of an average American’s family’s net worth and fully 60% among our middle class, the statistics around homeownernship further delineate the racial schisms of American wealth. Not only do blacks pay higher interest rates, have higher downpayments, have less access to credit, get turned down more frequently for loans no matter what’s controlled for, and pay what amounts to an 18% “segregation tax” because homes in black neighborhoods have much less equity than homes in white neighborhoods – but since 1970 black homes have appreciated in value roughly half as much as white homes.

Even Eminem seemed to have little sense of the irony that was invoked as his self-consciously white autobiographical film, 8 Mile, highlighted the hopeless plight of Detroit’s urban black community. The 8 Mile district was created in 1941, when a six-foot wall was built around a black enclave that was deemed unfit to accept loans from the Federal Housing Administration. This was “part of a system that divided the whole city, in theory by credit-rating, in practice by colour.” And so the segregation that emerged in Detroit “was not accidental, but a direct consequence of government policy.”

This policy of segregated mortgages became known as “red-lining,” and by the 1950s one in five black borrowers was paying interest at over 8%, while it was about impossible to find a white family paying more than 7%.

And yet this economic line extends far past that generation. The fact that blacks are foreclosing at a much higher rate than whites in the current crisis was predestined by the conditions of the loans they received, as banks turn down equally-qualified blacks much more often than whites, and forced blacks to pay higher interest on their loans. Housing values are indelibly color-coded, as the average value of a white house appreciates much quicker than a black house. All of this is snowballing into a collective institutional bias that cost black families at least $82 billion even before this current crisis began.

Hotlanta served as a case study for mortgage-based racism, as the Pulitzer-winning series in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution “The Color of Money” so aptly captured.

It showed how blacks were routinely rejected for loans which whites in a comparable economic situation were accepted for. And this phenomenon wasn’t isolated to one city, as a 1991 study showed that out of 6.4 million mortgage applications nationwide, even after income was controlled for – blacks were rejected twice as often as their white counterparts. However that wasn’t the worst of it, in urban centers such as Boston, Philly, Chicago, Minneapolis, blacks were rejected three-times more often than whites.

Even well-to-do blacks have been unable to escape from this institutional prejudice.

Wealthy black neighborhoods in the DC suburbs have a much tougher time getting loans than low-income white areas, and in Boston blacks living on the exact same street as their white neighbors and earning similar incomes found it much tougher to get a mortgage than their white neighbors. Joe Kennedy summed up the cumulative effect of this racial injustice well, describing “an America where credit is a privilege of race and wealth, not a function of ability to pay back a loan.”

The city of Baltimore partly captures how higher-rate loans to blacks have affected foreclosure rates, with several Wells Fargo loan officers testifying that they targeted “mud people” for “ghetto loans,” resulting in 71% of foreclosures in that city being made on black homes in recent years. And so, even when income and credit score are controlled for, across the nation blacks are more than three-times more likely than whites to have their home foreclosed and be thrown out into the streets.

America may have nominally advanced from “separate but equal,” but the reality of racial disparity still haunts the bottomlines of black mortgages and checkbooks, holding them back from fully embracing the dream we’re all supposed to share.

The very idea of what it means to be poor is color-coded, as while 1 in 3 blacks live in poverty, less than 1 in 10 whites do. And yet the very definition of poverty itself now varies to the point of absurdity, since “poverty level whites control nearly as many mean net financial assets as the highest-earning blacks, $26,683 to $28,310. For those surviving at or below the poverty level, this indicates quite clearly that poverty means one thing for whites and another for blacks.”

The impact of these facts have echoed across generations, as nearly three-quarters of all black children grow up in homes with no net financial assets. That’s nearly double the rate of white kids. And nine in ten black kids grow up in homes without enough monetary reserves to last more than three months at the poverty line if their income were to drop, roughly four times the white ratio.

Nearly any way you look at it, our current economic crisis is impacting our poor black communities much more acutely than our poor white ones. The most obvious indicator is the still skyrocketing unemployment rate, which for young black males is now twice as high as their young white counterparts.

But simple unemployment doesn’t capture the full scope of economic distress, to understand where we are now you have to take a look at where we’re coming from.

Following the Civil War the earliest anti-drug laws were passed in some states, banning the consumption of alcohol. But not, of course, for everyone. Whites could drink as much as they pleased – as well as use opiates and cocaine, but if you were a minority in much of antebellum America you were prohibited from imbibing or using any drug at all.

At the time it was a widely held belief in American politics that some races, bless their brown souls, simply couldn’t control themselves. Furthering the codification of this perception, in 1901 Henry Cabot Lodge spearheaded a law in the U.S. Senate banning the sale of liquor and now opiates as well to all “uncivilized races.”

In this case, “uncivilized” was synonymous with “dark.” At this point in American history, whites could get as drunk, high, or smacked as they wanted – while the brown-skinned members of American society were completely banned from consuming any intoxicant.

Throughout the first half of the 20th Century, any violence carried out by a black man against a white could be attributed to the commonly-held caricature of a “cocaine-crazed negro.” Newspaper headlines screamed of coked-up black criminals who were SHOT BUT DON’T DIE! and policemen claiming that WE NEED BIGGER BULLETS! because their current caliber wasn’t large enough to stop the crack-crazed negroes they routinely came up against in the line of duty. It was actually this specter of THE COCAINIZED-NIGGER that led to police nationwide to upgrade their guns from .32 caliber to .38 caliber.

However blacks weren’t singled out as a racial minority, the first anti-marijuana laws targeted the wave of Mexican immigrants who were spreading across the American South. They were seen, then as now, to be stealing jobs and government resources from resident whites, and so politicians from that region of the country first banned marijuana use by minorities alone and then eventually altogether.

Nixon’s public claim that the War on Drugs was primarily a response to the growing number of addicted veterans was at best a lie of omission. Taking into account past legal precedent, and the fact that American urban centers were being wracked by a series of seemingly unending race riots, it becomes self-evident that the War on Drugs was simply another page in the story of American anti-drug laws that have always been rooted in racism.

Then in 1973, with Nixon desperately attempting to spin his way out of Watergate, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller passed a set of laws that were soon mimicked by several other states and eventually the entire federal government.

They were minimum sentencing laws for drug crimes that, partially because they included a fifteen-year prison term for possessing even a small amount of narcotics, were the harshest the country had ever seen. The per-capita prison population of the United States remained constant from 1930 to right around 1973, at which point the graph begins an exponential climb that grows steeper and steeper with every passing year.

Is all of this just coincidence, or is there demonstrable cause-and-effect at work? Are things bad enough to cause the Department of Justice to deliberately massage its own data, effectively removing mixed-race prisoners from their statistics entirely?

These counter-narcotics laws that, both by design and in practice, fueled an explosion in our prison population – a population which started disproportionately black – with 90% of those incarcerated under the Rockefeller laws either Latino or black – and only growing to become more so as the years passed. Between 1979 and 1990 blacks made up a steady percent of our overall population, but between those same years blacks went from making up 39% of our drug-related prison population to 53% of it.

Today that number’s down to 51.2%. An improvement, but hardly.

Through the 1980s this disparate growth was fueled by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, one of the hundreds of crime bills passed by state and Congressional legislatures in the 1980s and 1990s. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act imposed the first of the mandatory minimum sentencing laws, here five-years in prison without chance of parole for anyone caught selling a substantial-enough amount of heroin, methamphetamine, marijuana, or cocaine. This last drug, cocaine, had a unique provision.

You’d receive the same unparolable five-year sentence for selling either 5 grams of crack cocaine as you would selling one-hundred times that much – 500 grams – of powder cocaine. Crack and powder cocaine are pharmacologically the exact same drug, there’re only two important differences. One is that crack cocaine is smoked while powder cocaine is snorted. The other is a bit more telling. Powder cocaine was mainly consumed by whites, whereas crack cocaine was the form of choice for innercity blacks.

Critics, for good reason, blasted the law as shamelessly racist.

America introduced a solution to civil disorder and social injustice that wasn’t novel, it’s simply grown to become unmatched in scale. By 2003, the percentage of our population in prison dwarfed England’s level, our international neighbor whose culture and mores are closest to ours.

We have, proportionally, six-times the population locked up behind bars as our tea-sipping crumpet-munching cousins across the pond. For France and Germany, the difference approaches ten-times as many.

Our prison population has increased five-fold in just thirty years. In terms of the global population, we have just 5% of that but fully a quarter of the world’s prisoners. And these American prisoners have one common and inescapable denominator that you’ve almost certainly already stereotyped them with – but for good reason. The stereotype of the black male American prisoner is, among other things, an accurate reflection of reality.

Our prison system has created a nearly inescapable gyre of poverty and despair, as other than race the most unifying characteristic of our prison population might be that some 50% of American prisoners are both illiterate, and have a family member who’s also been incarcerated at some point.

If anything whites use drugs at a slightly higher rate than blacks, and yet two-thirds of those imprisoned for drug possession are black, and the rate of black drug arrests is four-times the white rate. Nearly half of all drug arrests in America are for simple marijuana offenses, and during the ’90s arrests for simple marijuana possession accounted for almost 80% of the increase in drug arrests. These statistical realities should do much more than stagger you.

If you’re black – they terrify you.

Numbers aside, there’s absolutely no way spending time in prison pacifies someone.

Getting a man to kill someone right in front of them is surprisingly tough to do. The US Army didn’t get the formula right until Vietnam, when it combined the modern psychological principles of classic and operant conditioning, along with heavy doses of desensitization to violence and the appropriate levels of cultural and moral distance.

Our modern prisons, while not using classic or operant conditioning, appear to be reaching the same ends. Not only does increased incarceration raise the rate of violent crimes at the community level, but sticking someone in jail desensitizes them to violence and increases their level of cultural, moral, and social distance from anyone not in their own race.

No where in the modern world is someone more forced to “practice thinking of a particular class as less than human in a socially stratified environment,” a crucial step in becoming prepared to take someone’s life. It is extremely difficult to survive in most prisons without at least loosely aligning yourself with whatever gang your race corresponds to, and steering well clear anything beyond cursory or institutionally-forced interaction with members of another race.

Although America’s five-fold per-capita increase in the incarceration rate hasn’t seemed to have increased the overall level of violent crime, a study released in 2002 revealed that without the advances in medical technology that we’ve made since 1970 the murder rate would be between three and four times higher than it is today.

And upon their release, prisoners often become ineligible for public housing and are denied welfare. So getting a job and trying to find a legitimate way to support themselves is far from easy for ex-cons, more often then not they feel forced to go back to a life of crime to support themselves and any family they might have.

Unemployment rates as high as fifty-percent are frequently cited by those who have researched and followed the lives of former prisoners. One recent study put the unemployment rate at 60% in the first year after release, and another survey found that two-thirds of the employers surveyed in five large cities would never hire an ex-con. Having to state that you’ve been incarcerated on your job application means that any jobs beyond the most menial and low-paying will likely remain out-of-reach. And in today’s turbulent economic times, when even those with advanced college degrees have trouble finding any kind of paid work, the prospect for an ex-con is even more grim.

Due to the incredibly high concentration of blacks in the American prison population, the hope-numbing impact of being held in prison and then being hard-pressed to find employment afterward enforces “the stigma of race [that] remains the unmeltable condition of the black social and economic situation.”

Racism is generally understood in America to have fallen to an all-time low. But this is an illusion, created because our prisons and the hundreds of thousands of black men inside of them are built at sites unseen.

A “subtler and more covert” racism has been enabled as prison populations artificially bend racially specific underemployment rates as “mass incarceration makes it easier for the majority culture to continue to ignore the urban ghettos that live on beneath official rhetoric.”

The Civil Rights movement was marked by dozens and dozens of indelible images of racism that were carried in the media each day – black children being marched past an angry white mob into a newly segregated school, police dogs being sicced on peaceful black protesters, burnt-out remains of bombed black churches, one black man behind a pulpit preaching of Christian love and patience and another black man punctuating with his fist the need for angry black action, crowds full of college students both black and white being sprayed at times by firehoses and other times by bullets.

We’ve all seen the living, breathing, killing reality of racism in the 1970s. None of us now are able to see its existence now, because racism no longer lives on the front pages of our newspapers and on our evening news – instead it’s been suffocated inside poured concrete walls which rise and fall in invisible existence, locked safely out of sight.

“America will never be destroyed from the outside. If we falter and lose our freedoms, it will be because we destroyed ourselves.”

-Abraham Lincoln