the racism instinct

Could humanity's propensity for out-group hate be rooted in more immunologically perilous times?

Love at first sight. A feeling of fate, destiny, of Meant to Be. We’ve all been there, enthralled by a sense that in someone else we’ve found a missing piece of ourselves. From the time we’re kids, we’ re told that this is the most wonderful compulsion in the world, that we should all be so lucky to have love sweep into our lives and wash away all of our fears and hesitations with its tempestuous embrace.

And yet, like all things, love too has a hidden side that we’d rather tell ourselves isn’t really there at all. But confronting it isn’t a simple matter, because that requires admitting to yourself that there’s an insidious stranger who influences the choices you make and beliefs you hold in ways you’d rather not think about too much.

Especially when what might be the worst pandemic humanity has ever faced is stretching out to embrace all of us, having already gutted one of the oldest civilizations on the face of the earth.

10,000 years ago something funny began to happen within the human genome. We didn’t know it at the time, but minute changes that would haunt every generation to come were slowly and imperceptibly unfolding inside each and every one of our ancestors.

Almost like flipping a switch, what had once been a steady rate of selection suddenly increased as the novelty of agricultural living and an immensely increased population that inevitably followed from the increased food supply allowed alleles that had been quietly lurking in the background to emerge, and “the pace of change accelerated to 10 to 100 times the average long-term rate.”

These changes were driven at least in part by the development of agriculture, the domestication of both plants and animals. Some human intestinal tracts retained the enzymes necessary to digest lactose as adults, others adapted to deal with a grain-heavy diet. Although agriculture wasn’t the only factor and there were certainly other forces at play, we do know, without question, that 10,000 years ago mutations in our genome began to accumulate at a pace never before seen in human prehistory.

Life as we’d known it would never be the same.

The proliferation of agriculture, both domesticating animals and growing crops, brought seismic and irreversible changes to early human societies. One impact was that that populations suddenly became much denser, another was that humans began to interact much more frequently and closely with domesticated animals. These two factors – population density and our cohabitation with the creatures that would become our beef, pork, and poultry – allowed contagious zoological diseases to kick a firm foothold into human societies and marked the beginning of an arms race between pathogens and immune systems that’s still ongoing.

“Diseases such as malaria, smallpox and tuberculosis, among others, became more virulent,” and we’ve since traced the flu back to ducks, pigs, and geese as its original hosts. Additionally, barnyard animals like cats, rats, horses, cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and birds have all played roles in transmitting – in no particular order – anthrax, rabies, tapeworms, plague, chlamydia, and salmonella.

And, after a bit of time, one of the most noticeable changes of all occurred.

Somewhere along the Black Sea’s coast, a baby popped out and looked up at its parents with blue eyes. This novel mutation along the OCA2 gene codes for much less melanin, a reduction that had already begun as humans migrated away from the equator, but which didn’t manifest as blue eyes until roughly 10,000 years ago. This mutation has since propagated itself across some northern regions, and although it generally correlates with fairer skin, as some Berbers (carrying the same mutation down to North Africa) and some Melanesians (whose light eyes come from a different mutation) demonstrate – it doesn’t always.

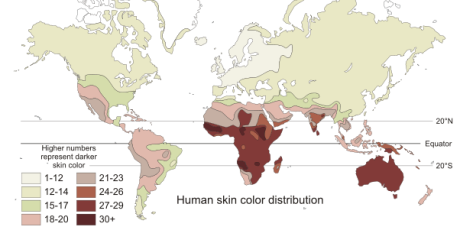

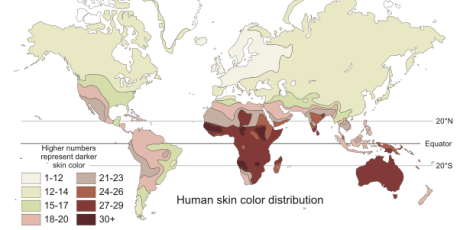

So as deceivingly decisive as the map below may seem, it’s important to keep in mind that the alleles – stretches of nucleotides that encode proteins – for skin pigmentation vary across the planet. Darker skinned Asian folks get their shading from different sections of their genome than African families. And those families – in most cases separated by thousands of miles and many thousands of years of selection – may happen to be roughly the same shade, but will likely be adapted to environments that are otherwise entirely different.

So although using the shade of someone’s skin as the primary trait to infer someone’s race may seem like a useful shorthand for heritage – it’s really very limited. And to be fair it should be mentioned that the concept of race is technically still contested in the life sciences. Plus there’s the confusion that inevitably creeps in when categories such as “Jewish” can encompass a national, ethnic, religious, and racial identity to someone – but only one, or just a few, of those categories for someone else.

And yet, broadly speaking, individuals with different continental ancestries do show correlated genetic differences and morphological characteristics, clinal as these often are. Furthermore, studies have shown that social categories of race such as “black” and “white,” categories that have been traditionally based on traits like skin color, do indeed have a biological component. In addition, through the use of statistical analysis, geneticists can often identify continental-scale clusters in humans which in many cases overlap with our social conception of race.

Since skin color is the most visible characteristic it’s often used as a shorthand for immutable distinction between large groups, yet if you peel the page back just once it becomes readily apparent that its far too broad a brush to legibly write on any individual genome.

Besides the fact that the shade of someone’s skin only gives us a general idea of where their ancestors might have lived, from Tiger Woods to Patrick Mahomes: Countless individuals embody the fact that this discussion will always be the loosely blurred reality of large numbers, not individual destiny. So all the map below really provides is an overlay of the various ways homo sapiens’ genome can decide to cope with sunlight levels as far as skin color goes, which may or may not correlate to other genomic overlap and should never be seen to indelibly encode individuality:

And yet this reduction in pigmentation did have one obvious, superficial, universal biological trigger: we’ve known for a while that the fairer your skin, the more vitamin D you’ll produce when it’s hit with sunlight.

And in the past few years new information has emerged, in turns out that “vitamin D is crucial to activating our immune defenses and that without sufficient intake of the vitamin, the killer cells of the immune system – T cells – will not be able to react to and fight off serious infections in the body.” Without enough vitamin D in our bodies, our immune systems simply cannot function. Labeling it a “vitamin” is actually a bit of a misnomer, it’s actually a hormone that functions as:

”…a potent antibiotic. Instead of directly killing bacteria and viruses, [vitamin D] increases the body’s production of a remarkable class of proteins, called antimicrobial peptides. The 200 known antimicrobial peptides directly and rapidly destroy the cell walls of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, including the influenza virus, and play a key role in keeping the lungs free of infection.”

Additionally it turns out vitamin D “seems important for preventing and even treating many types of cancer… Four separate studies found it helped protect against lymphoma and cancers of the prostate, [colon], lung and, ironically, the skin.”

And vitamin D isn’t just another hormone, in fact it’s tied in to our very humanity. Or at least our very simian-anity, as vitamin D’s vital role in primate immunology emerged within our genome over 60 million years ago, and carries a functionality that is unique to us and our furrier brethren – no other animal on earth except primates shares the DNA which ties vitamin D to antibacterial peptide synthesis.

Besides just helping fight off infection, it prevents the autoimmune overreaction of the body fighting itself, and so it “may enable suppression of inflammation while potentiating innate immunity, thus maximizing the overall immune response to a pathogen and minimizing damage to the host.”

Much of what we now describe as racial groups emerged as a direct consequence of migrating into more northern environments since lightened skin gave dense agricultural communities the strengthened immune system they needed to fight off the lethal pathogens and parasites that became an increasing threat to crowded early human societies. And as Guns, Germs, and Steel outlined, as different racial groups domesticated and interacted with different animals, they developed communal immunities to discrete sets of diseases:

“Disease-causing pathogens—viruses, bacteria and protists—have geographies, both in terms of where they can be found and how common they are within those regions. The consequent map of malaise and death affects many aspects of the human story”

Ancestral communities in Eurasia, Africa, the Americas, and Southeast Asia were each exposed to unique biological threats, depending on the geographical and environmental niche they inhabited and the animals they domesticated. Although there was some overlap, their exposures were still discrete enough so that when one community did come into contact with the other, widespread pandemics of the strangers’ diseases often occurred and entire populations were wiped-out.

Living shoulder-to-shoulder with each other and with their newly domesticated livestock, disease became a much bigger threat than it’d ever been to early hunter-gatherer communities. This immunological legacy is still with us, as different racial groups express different rates of a vast array of common diseases to this day.

So what does any of this have to do with love? Well, understanding that requires a quick introduction to that insidious stranger inside each and every one of us.

All of us would like to think that the choices we make are very much our own, that although our moral compass may at least partially be a biological construction, choosing whether or not to follow it is still the reasoned product of our own carefully applied free will and a direct reflection of our unshakable individuality. And yet it turns out that not only are our minds inevitably influenced by the behavior and suffering of those around us, but that Reason has much less than we’d like to think to do with our decisions: Our choices are far more tied to the most primitive emotional parts of our brains than our conscious awareness would like us to think.

And perhaps there’s no better way to demonstrate this than by looking at patients with damage to an oblong tangerine-sized region of our brains just behind and above the bridge of our nose, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

Enough damage to this region can drop your emotional function to zero, meaning you could “look at the most joyous or gruesome photographs and feel nothing.” Which also means that although you’d still be able to answer abstract questions about morality in others’ lives, in the sense of filling in the blank of a social equation, in your own personal life your decisions become so amoral or foolish that you alienate your loved ones, lose your job, and your entire life falls apart.

This, inevitably, led the neuroscientists who noticed these changes to conclude that “gut feelings and bodily reactions were necessary to think rationally” and that without a functioning ventromedial prefrontal cortex it’s impossible for us to integrate these emotional gut feelings with conscious thought. So without this region of the brain working properly “every option at every moment felt as good as every other.” As it turns out, it’s this most primitive, instinctual, split-second region of our brains that leads the charge into decision-making.

And so “moral reasoning is mostly just a post ad hoc search for reasons to justify the judgments people had already made,” meaning that by the time you notice yourself weighing options and thinking about the best path, you’ve really already decided subconsciously and emotionally, and are just spinning excuses and justifications to yourself.

So if you continually put yourself in emotionally-charged situations, it’ll only be a matter of time before this elephant of subconscious emotional desire shifts beneath you and takes a step down a path that can ruin your life and the lives of those around you. And it’s always this dominating emotional elephant of rapid instinctive moral judgments that’s in control, the best that the contemplative reasoning rider on top of this primal beast can do is to come up with rationalizations after the elephant has sated its desires.

Sometimes these desires are perfectly healthy for ourselves and the society around us, at other times they leave feelings and lives trampled behind. Which means that although the rider can do his best to look into the future in an attempt to steer the elephant down the best path, more often than not he’s left trying to serve as the elephant’s spokesperson without really knowing what the elephant is thinking and “fabricating post ad hoc explanations for whatever the elephant has just done” while justifying whatever course it feels like taking next.

On a social level this had an obvious impact, “once human beings developed language and began to use it to gossip about each other, it became extremely valuable for elephants to carry around on their backs a full-time public relations firm” to provide an acceptable justification for everything we do. Because after all, “reason is the servant of the intuitions. The rider was put there in the first place to serve the elephant.”

But this elephant isn’t always galloping along blind to everything except its own whims. Since although “we make out first judgments rapidly, and we are dreadful at seeking out evidence that might disconfirm those initial judgments … friends can do for us what we cannot do for ourselves: they can challenge us, giving us reasons and arguments that sometimes trigger new intuitions, thereby making it possible for us to change our minds.” So although “many of us believe that we follow an inner moral compass … the history of social psychology richly demonstrates that other people exert a powerful force, able to make cruelty seem acceptable and altruism seem embarrassing, without giving us any reasons or arguments.”

As humans, we see our behavior as far more noble then it actually is, and assume that an outside other wouldn’t live up to the standards we’ve set. But as Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman chronicles in the book dedicated to his late friend, Thinking, Fast and Slow, after we take a careful look at just how subject to outside influence our own behaviors and thoughts are it becomes impossible not to acknowledge just how malleable we really are.

Maybe it won’t come as a surprise to learn that being prompted with a story about cleaning dirty clothes will make it much more likely for you to complete W __ __ H and S __ __ P as W A S H and S O A P as opposed to W I S H or S O U P. However it should be at least a small surprise to learn that a story about betraying a friend, a “dirty deed,” will have the exact same effect on your word completion as a story about dirty clothes.

This contextual prompting effect is known as priming, and its implications for human behavior and our own free will go far beyond simple stories and word choice. Priming can escape the page, as students who were asked to unscramble sentences that included words like forgetful, Florida, bald, gray and wrinkle in them and then asked to walk down a hall to another room ended up walking significantly slower than students who weren’t primed with words associated with the elderly, even though the sentences never actually had the word old or any reference to speed in them – only words that would create a subconscious association with oldness.

And, maybe even more surprisingly, the converse held true as well: when instructed to first walk at one-third their natural rate, a speed more suitable for a grandparent, students then recognized worlds like forgetful, old, and lonely much more readily, even though their walking instructions were explicitly about speed – not age.

In a related set of experiments, people were told they were testing the quality of new headphones by listening to radio editorials with them. During this supposed testing, to test for sound distortions they were instructed to repeatedly either shake their head from side to side or nod it up and down. Those who had been nodding yes tended to accept the opinion expressed in the editorials they were listening to while those shaking their heads no tended to reject it.

So our physical motions can unconsciously affect our thoughts, and vice-versa, and yet priming goes well beyond physical gestures. Our surroundings will inevitably affect other behaviors too, as studies of voting patterns have shown that support for propositions to increase school funding is far greater when polling stations are located inside schools, and even exposing voters to school-related images causes support for educational initiatives to rise. Maybe that makes it seem like priming mostly has a positive influence, however when it comes to money and priming, its double-edged nature becomes evident.

Experiments which subtly prime participants with anything from financial terms to Monopoly money stacked on the table do make people spend twice as long trying to solve a tough problem instead of giving up on it and show more self-reliance, however they also became more selfish and less helpful to someone in need. And placing a banner with watchful eyes on it above an office “honesty box” designated to take payments for caffeinated drinks will make donations spike significantly when compared to a banner with festive flowers on it being hung – great if you’re collecting the money, costly if you’re giving it.

And so at this point, “you have now been introduced to the stranger in you, which may be in control of much of what you do, although you rarely have a glimpse of it.”

This stranger “contains the model of the world that instantly evaluates events as normal or surprising,” reflexively producing a web of subconscious associations following every stimulus since it’s “the source of your rapid and often precise intuitive judgments. And it does most of this without our conscious awareness of its activities.” As Dr. Kahneman explains while channeling Dr. Frankenstein:

And not only does this insidious stranger hold sway over practical matters, he also reaches in to our very sense of good and bad, of right and wrong. But maybe most tellingly, our values can change when there are infectious agents around.

Students asked to ponder morally hazy behavior – from relatively innocuous things like fudging a resume or returning a lost wallet, to more unpalatable decisions like unethical journalism or cannibalizing fellow plane crash survivors – were far more harsh with their moral judgments when seated around food stains or chewed-up pens, or when exposed to fart spray, which is exactly what it sounds like.

When you’re exposed to possible sources of contagion you’ll also be harsher when evaluating behavior that isn’t undoubtedly immoral but just doesn’t sit right, and more negatively judge a man who, for instance, fornicates on his grandmother’s bed – not while she’s there, just while housesitting for her. After disgust’s been elicited you’ll become “more likely to endorse biblical truth than those not subjected to the polluted air.” Placing someone next to a hand-sanitizer dispenser will make their moral, fiscal, and social opinions more conservative.

And this phenomenon applies directly to our criminal-justice system as well, as “a study of people serving as mock jurors found that those highly prone to disgust were most inclined to judge ambiguous evidence as proof of criminal wrongdoing, to impose stiffer sentences, and to see the suspect as wicked.” But maybe most disconcertingly, this same study was also replicated with law students, police cadets, and veteran forensic experts.

So not only are the choices that can land you in prison subject to influences operating quietly and insidiously beyond the ken of our free will, the choices of those who will decide your fate lay at least partially outside of theirs. But this doesn’t excuse immoral or illegal behavior, it simply means that you have to be aware of the situations you’re putting yourself in and the influence that the seemingly innocuous can have. The lyrics you listen to, the jokes you make, the television shows you watch, the lifestyle you idealize – all of these play a subtle role in swaying your actions, carefully weaving an inescapable diaphanous web around everything you do.

Your choices aren’t made in the moment it seems they are. The circumstances you place yourself in and the context you surround yourself with, the words and symbols and values you make part of your life, combine to begin priming your subconscious and forcing it to continually decide which of the options at hand not to chose, and influence your eventual decisions like implanted hypnotic suggestions – prompting behavior which may well never have happened without their influence.

On some level it’s the choice to continually place yourself in a situation where one too many beers, one changed mind, one conflicting story are all it takes to put you behind these bars that matters – not what may or not have actually happened once that story has already begun to be told.

There’s even a theory that culture itself and all the behaviors it encompasses “originated as a behavioral adaptation to an epidemic-filled past.” So from spicing our foods and avoiding outsiders to showing affection to burying the dead – there may not be a single culture touchstone left unmarred by immunology’s influence. And these immune behaviors “once developed, stick around because the people who indulge in them are less vulnerable to infectious diseases. The behaviors, passed down through the generations, become entrenched.”

And it’s nearly impossible to overstate the effect contagious diseases have had across our societies, from the Spanish Flu and the Black Death drastically altering the world’s demographics, to the reality that it was infectious diseases, not violence, that killed off an estimated 90% of Native Americans after Europeans arrived. Although the European contamination of the Americas are the best example of this sort of accidental immunological genocide in recent history, the folklore shared by every culture on earth warns of the mysterious and dangerous Other that’s manifested as monsters and other mythical threats often depicted as diseased creatures: pock-marked boogiemen, decaying zombies, slavering werewolves, pale and sickly vampires.

But even if the anthropological arguments don’t convince you, the prevailing theory is that sex originally evolved on the unicellular level so many billions of years ago as a way to outwit pathogens: It was only by mixing and matching chromosomes to form a sort of variegated genetic camouflage that the very first life on Earth was able to stay one step ahead of the viruses and bacteria set on killing them.

So arguing that sex and immunology have no relationship at all in humans would require ignoring the fundamental nature of life on the planet. And as it turns out, humans do in fact appear to have a fairly fine-tuned way to filter the best mate choices, and subconsciously steer clear of the sort of accidental genocides that have haunted our ancestors.

Within the past several years everyone from Cosmo to Nature has reported on the results of a surprising study: women can, it would seem, smell who they’re attracted to. Bags containing t-shirts that various men had worn while exercising served as sweaty glass slippers, women were asked to rate the attractiveness of the scent contained in each bag – every white t-shirt was exactly the same except for the odor of the man who’d worn it. Women rated each bag and went on their way, never to learn anything more about the prospective mates than what their used laundry smelled like. And when researchers went to work trying to figure out why women made the choices they did, a surprising and consistent link was found: women are attracted to men whose major-histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes best complimented theirs:

Women’s preference for MHC-distinct mates makes perfect sense from a biological point of view. Ever since ancestral times, partners whose immune systems are different have produced offspring who are more disease-resistant. With more immune genes expressed, kids are buffered against a wider variety of pathogens and toxins.

MHC genes are the gatekeepers of our immune systems, they determine white blood cell function and decide whether or not organs will be accepted for donation – regulating whether or not a new host will accept a donor organ as its own or attack it as an outside contagion. The better suited your MHC genes are to fighting the pathogens present in your environment, the healthier you’ll be.

And not only healthier, but more intelligent too. A study of IQ scores and infectious disease found that both internationally between nations and nationally between states, IQ levels correlate more closely with the rate of infectious disease than any other factor. Given how biologically taxing it is for children to fight off disease, and the fact that our brains suck up 90% of our energy as newborns and one-quarter of our energy as adults, it stands to reason that healthier societies end up more intelligent on the whole and that instincts which select for healthy progeny would emerge.

So when it comes to picking a mate who will pass half of their MHC genes onto your child and largely decide the suitably of their immune system to the environment, the trick is determining exactly what “compliment” means, as researchers found that “women are not attracted to the smell of men with whom they had no MHC genes in common. ‘This might be a case where you’re protecting yourself against a mate who’s too similar or too dissimilar, but there’s a middle range where you’re okay.’”

Who would have MHC genes that would complement yours? Members of a population that underwent similar immunological pressures as your ancestors – but not exactly the same. Not a nuclear family member, but maybe a close-ish relative like a second or third cousin – certainly someone whose ancestors adapted to similar pressures created by the diseases that became so prevalent in crowded communities that were in close contact with each other and the livestock they raised.

Pressures which began to burgeon roughly 10,000 years ago, which is when our first blue-eyed ancestor was born and when racial differentiation began to emerge in earnest. And so it would make a certain amount of biological sense for us to be biologically compelled to make babies with those who smell like they share some relatively recent ancestry with, to ensure that our kids have an immune system that’s suited to the immunological pressures they would have encountered:

”Body odor is an external manifestation of the immune system, and the smells we think are attractive come from the people who are most genetically compatible with us.” Much of what we vaguely call “sexual chemistry,” is likely a direct result of this scent-based compatibility.

And this compatibility isn’t outwardly expressed only in scent, we also wear our MHC genes somewhere even more obvious than our sleeves: directly on our faces.

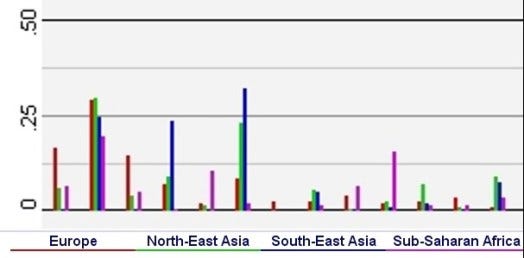

Multiple studies have shown links between the range of human MHC genes and facial appearance, as well as MHC genes and perceived attractiveness. It would follow that simply by looking at a member of another race, we would immediately know on an instinctual level that their MHC genes may well be wildly dissimilar to our own. And an examination of the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s online database reveals these disparities throughout our MHC genes. As this probabilistic selection of some of the HLA-A alleles illustrates, although some alleles occur at similar rates, the odds that many of them will occur varies widely across the MHC region of our genomes:

Each grouping represents a different HLA-A allele: 1, 2, 3, 11, 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33

All of this makes a tremendous amount of sense, an instinct to create offspring with someone who is going to provide your child with the best odds of having a robust immune system would have been vital for any community that was under significant pressure from disease. And it’s important to keep in mind that this instinct would have begun to emerge 10,000 years ago, long before any sort of antibiotics or sterile surgery. Medical science develops incredibly quickly, even just 150 years ago doctors didn’t even realize they should wash their hands before jamming them up inside someone to pull a baby out. Modern medicine has arguably rendered this instinct obsolete in practical terms, and yet it may still be wired into us as part of our primitive heritage.

But just because something’s an instinct doesn’t by any means make it Right.

We also have instincts for violence and promiscuity that would cause our societies to implode if they weren’t regulated by human reason and rational decision-making. Human societies are epic practices in not embracing our basest instincts, individuals are encouraged to do their best not to act like animals. And yet all that said, it doesn’t make the instinct to breed with someone who’s going to provide your brood with the best suited immune system for the environment any less real, or any less a part of who we are.

So human females indicate a preference for mating with someone who shared a similar ancestry as themselves, but would it necessarily mean a distaste for outsiders? At least for ovulating women, yes it would.

Turns out women who are fertile exhibit a strong implicit bias against men from other races. While ovulating women were more attracted to men of their own race who were perceived as physically imposing, the opposite was true if the man was a member of a different racial group. So not only are we drawn to members who share a similar ancestry as our own, but human females may be unconsciously repelled by members of other races when they’re fertile.

An increasingly common refrain in America had been that it’s easy to pretend that racism is dead and gone, at least until a black guy knocks on your door intending to take your daughter out on a date. This continued prejudice was dubiously enshrined in our laws against miscegenation, which were the last racist laws to leave our books and weren’t ruled unconstitutional until a generation after Brown vs. Board, at which point only 20% of Americans were in favor of legalizing interracial marriages. And yet despite that ruling, Alabama had a law against interracial marriage on the books until 2000, and even then 40% of Alabamians voted in favor of it.

African-Americans may be especially prone to be discriminated against and subconsciously perceived as an out-group, as recent analysis of the human genome have indicated that most sub-Saharan Africans carry traces of ghost ancestors, whose genomes don’t appear in any other population on earth.

What genetic legacy the this ghost genome, or lack of it, has had on humanity is still unclear – however what’s inarguable is that those of us with heritages that reflect different environmental and subsequently immunological pressures do in fact have profoundly different immunological markers in our genomes, one of which is the divide between those of with traces of those ghost ancestors and those without.

Of course this shouldn’t create a distinction that should be honored or celebrated, our humanity is nothing if not shared. But maybe this genetic legacy stirs something irrational and subconscious, whose impact appears over and over again in the ever-present irrational hatred and fear that too often haunts and rends our societies. Maybe, just maybe it’s worth exploring the idea that racism may have some biological basis – not as a road to validating it, but as a way to drag an irrational boogeyman out into the light.

Not as a way to validate racism, but instead as a way to fully understand and then combat it. After all, it’s hard to miss that “selective pressures have consistently sculpted human minds to be ‘tribal’ and group loyalty and concomitant cognitive biases likely exist in all groups.” And as it turns out, there are some fairly well-trodden biological pathways that indicate racism should be addressed as a bias that isn’t just about senseless cultural hatred so much as misplaced biological anxiety.

One of which gets directly to the point.

Although women clearly have a much stronger sense of smell and are much more attuned to finding partners with compatible MHC genes, men are still aware of this interaction and their opposition to members of an outside race mate-pairing with sisters and daughters who share their genetic code makes evolutionary sense: They want their communal familial gene pool to stay immunologically robust. Additionally, the apparent instinct of being able to smell and perceive a stranger’s MHC genes may easily have caused an instinctual xenophobia to develop, since someone with vastly different MHC genes would often be harboring pathogens that you and your entire society’s immune systems would be utterly defenseless against.

And it should be noted that it’s not just fertile females who appear to exhibit a prejudice against members of other races, recent research into implicit bias indicates that most white folks are subconsciously pretty damn racist. Or at least their strangers are, since all of these studies rely on the kind of sneaky subconscious bias our strangers embody.

Research at Yale supports the idea that many whites are unconsciously biased, whether they admit it to themselves or not, and no matter how many black friends they have. The following experiments required a rather complicated set-up, but to get an idea of what your own implicit and unconscious feelings about race actually are, you can take a few minutes at: Harvard’s Implicit Association Racial Test.

In Yale’s first experiment, when white test subjects either read about or watched a video of a white guy calling a black man a “clumsy nigger” or saying “I hate when black people do that” after being accidentally bumped into, they frequently claimed they would have confronted the guy making the racist remark if they’d been there, and at least 75% of them said they’d rather work with the black guy in the scenario than the racist white guy.

But when subjects were actually in the room for the above event and the racial epithet was spewed in their presence, none of them actually spoke up and 71% of them said they’d rather work with the openly rather racist white guy than the black man. But it gets a lot worse, as demonstrated by one recent study conducted over the course of six-years at Stanford:

…that showed [white] study participants words like “ape” or “cat” (as a control) and then a video clip of a television show like “COPS” in which police are beating a man of unknown racial identity. Then, the researchers showed the participants a photo of either a black or white man, described him as a “loving family man” yet with a criminal history. They then asked participants to rate how justified they thought the beating was. Those who believed the suspect was black were more likely to say the beating was justified when they were primed with words like “ape.”

Leading researchers to the uncomfortable conclusion that “whites subconsciously associate blacks with apes and are more likely to condone violence against black criminal suspects as a result of their broader inability to accept blacks as ‘fully human.’” But all of these subjects were at least college-aged, perhaps nothing instinctual is going on and they’re just displayed culturally learned behaviors. Well, if that were the case – why are nine-month old babies racist too?

Turns out white nine-month old babies with little or no previous contact with African-Americans have trouble telling black faces apart and don’t register emotions on black faces as well as emotions on white faces:

“These results suggest that biases in face recognition and perception begin in preverbal infants, well before concepts about race are formed,” said study leader Lisa Scott in a statement. The shift in recognition ability was not cultural, rather a result of physical development.

Although, curiously, five-month old babies seem to process faces from either race the same way. But it’s important to note that babies don’t develop a fear of height or a fear of strangers until they’re seven-months old. Five-month old babies might seem to be processing “faces” of different races the same way, but without a fear of strangers it’s a bit hard to argue that their brains have developed to the point where they can understand the concept of personhood in the first place. And without any fear of height it would seem their brains haven’t yet reached the point where any fear instinct at all would have kicked in.

And perhaps the strongest and most disturbing support for the idea that racism is at least partial a subconscious biological bias comes from the language of genocide. Targeted minority groups are referred to as zoological disease vectors like cockroaches or vermin, are said to be dirty and harbor contagions, or accused of contaminating a purer race. If a subconscious immunological bias has anything at all to do with why this genocidal propaganda seems so insidious and potent, getting rid of it can only help prevent the worst of humanity from rearing its head.

Plenty of research has been done into racism as a cultural reality, but very little has examined its potential roots as a naturally occurring instinct that may be inexorably rooted in our biology. And even if you haven’t been on X-Box Live or an internet messageboard recently, if you take a moment to look at the data it become readily apparent that American society is still unarguably organized largely along racial lines:

– Only 14% of all illicit drug users are black and yet blacks make up over half of those in prison for drug offenses

– A black child is nine-times more likely than a white child to have a parent in prison

– A black man is eight-times as likely as a white man to be locked up at some point in his life

– The average black family has eight-cents of wealth for every dollar owned by whites

– Blacks are more than three-times more likely than whites to have their home foreclosed and be thrown out into the streets.

What if the policies that have created these abject discrepancies aren’t simply a result of learned cultural behavior, but are to some extent rooted inside of our genome? If an aversion against members of outside racial groups has a strong biological component and isn’t simply cultural, the fundamental interactions of societies with mixed racial groups and the policies they enact should be very carefully reexamined.

And as the Wuhan Strain of coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, hitches rides on jet-planes and cruise-ships on an inevitable journey out of China and into our backyards – we might be facing our toughest test yet. Because never will racism seem so easy and reflexive than when you think it’s protecting you and your family from the horrific unknown. But fighting it will require every civilization on earth to trust each other, to communicate, to work together to stop what might be the most potent threat we’ve ever faced.

In a perfect world our children would be judged by the content of their character, but if the color of their skin is linked to a subtle unconscious instinct for racism within each and every one of us, we aren’t going to get anywhere until we bring this vicious racial chimera out from its genomic cave and deal with it directly.

“Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscientious stupidity”

– Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Dan Sirotkin recently returned from a state-sponsored sabbatical studying the effects of the War on Drugs and prosecutorial overreach on America’s most under-served communities by serving as a prison classroom’s special education tutor, after a brief stint scrubbing toilets. You can read about those adventures here.

Prior to that he parlayed his Harvard degree and time at the NSA to write about the interwoven intersection of asymmetric warfare and terrorism, concluding that the greatest threat to American stability will emerge from inequalities that can nearly all be traced back to our carceral system.

This is brilliant! I have had some similar thoughts, but have not had time to see where I could take the idea.

https://www.bloombergquint.com/gadfly/implicit-bias-training-isn-t-improving-corporate-diversity

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-false-science-of-implicit-bias-1507590908

"Mr. Greenwald and Ms. Banaji now admit that the IAT does not predict “biased behavior” in the lab. (No one has even begun to test its connection to real-world behavior.)"

The creators of the implicit bias test admit they don't actually work and yet everyone's using them.